Originally

published in Professional

BoatBuilder by Steven Callahan

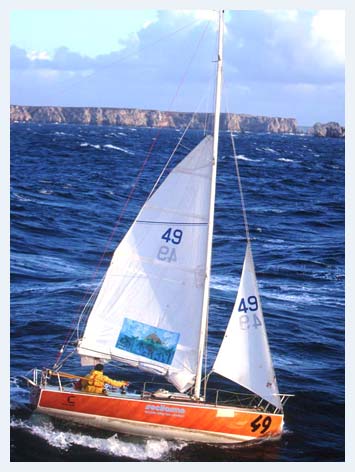

I first heard of Tom Wylie when his — yes, revolutionary

— AmericanExpress blew away the competion in the 1979 Mini-Transat

singlehanded transatlantic race. Express was like no other boat

in this innovative and competitive class; her 8' (2.4m) beam on

a 21' (6.5m) hull was radically wide, her 5' (1.5m) draft radically

deep, her 253 sq ft (23.5 sq m) of sail (expandable to 703 sq ft

[65.3 sq m] downwind when flown from poles as long as the boat)

radically large, and her 618 lbs (280.3 kg) of water ballast radically

eye-opening. Express' water ballast kept her on her feet when hard-reaching

and beating. In light airs and downwind, skipper Norton Smith dumped

the water to significantly reduce drag, giving her daily runs exceeding

180 miles — something deemed impossible at the time for a

21-footer. She has since logged more than 200-mile days. Wylie built

her tough hull using a “core” of stiff Western red cedar

and skins of strong and resilient Douglas fir. She's withstood numerous

ocean crossings. Hurricane Emily even ran her over in 1981, and

though she was knocked down repeatedly and even capsized, she finished

the crossing on her own bottom and with rig intact. This minuscule

skimming dish's 1979 victory immediately transformed shorthanded

grand-prix raceboats of all sizes and one could argue, foreshadowed

the trend toward wide-bodied contemporary hulls, as well.

Wylie

did not invent movable or water ballast. Movable crew have kept

boats upright since pre-history, and inanimate shifting ballast

appeared prior to the 19th century. The late great singlehander

Eric Tabarly, with designers Michel Bigoin and Daniel Duvergie,

created water ballast for Tabarly's Pen Duick V. in which he won

the 1969 San Francisco-to-Tokyo singlehanded race, but until Wylie's

American Express, designers failed to appreciate Tabarly's innovation.

Even Wylie missed it. Wylie: “I didn't know about Pen Duick

V until afterward, and she used quite a different system. Express

had a relationship to Tabarly's boat, but to say that I took Express

from Tabarly would be like saying I took cold-molding from International

14s." Certainly Wylie increased the role of water ballast.

Tarbaly's Pen Duick V carried only 11% of his boat's displacement

and 91% of its fixed ballast in water ballast, while Express could

haul 27% of her displacement and 140% of fixed ballast in liquid

form. Wylie

did not invent movable or water ballast. Movable crew have kept

boats upright since pre-history, and inanimate shifting ballast

appeared prior to the 19th century. The late great singlehander

Eric Tabarly, with designers Michel Bigoin and Daniel Duvergie,

created water ballast for Tabarly's Pen Duick V. in which he won

the 1969 San Francisco-to-Tokyo singlehanded race, but until Wylie's

American Express, designers failed to appreciate Tabarly's innovation.

Even Wylie missed it. Wylie: “I didn't know about Pen Duick

V until afterward, and she used quite a different system. Express

had a relationship to Tabarly's boat, but to say that I took Express

from Tabarly would be like saying I took cold-molding from International

14s." Certainly Wylie increased the role of water ballast.

Tarbaly's Pen Duick V carried only 11% of his boat's displacement

and 91% of its fixed ballast in water ballast, while Express could

haul 27% of her displacement and 140% of fixed ballast in liquid

form.

The hull shape of Wylie's Express also differed dramatically from

other ocean racers of the day. By the late 1970s, very beamy IOR

hulls had gained a reputation not only for great speed when sailed

flat with lots of crew, but also for dramatic spinning out and loss

of control when heeled. By comparison, the fair sections and full

forward shoulders on Express kept her running smoothly. As inverse

tribute to Wylie's success, the rulemakers immediately outlawed

Express by limiting future water ballast to 50% of fixed ballast.

Still, before being awed by the present-day “aircraft carriers”

that currently dominate singlehanded marathons like the Around Alone

and Vendée Globe races, we should remember that the basic

proportions of Wylie's design were every bit as radical and became

common on Mini-Transat racers more than a decade before they appeared

in the Open 50s and 60s.

|